Article Directory

Here is the feature article, written from the persona of Julian Vance.

*

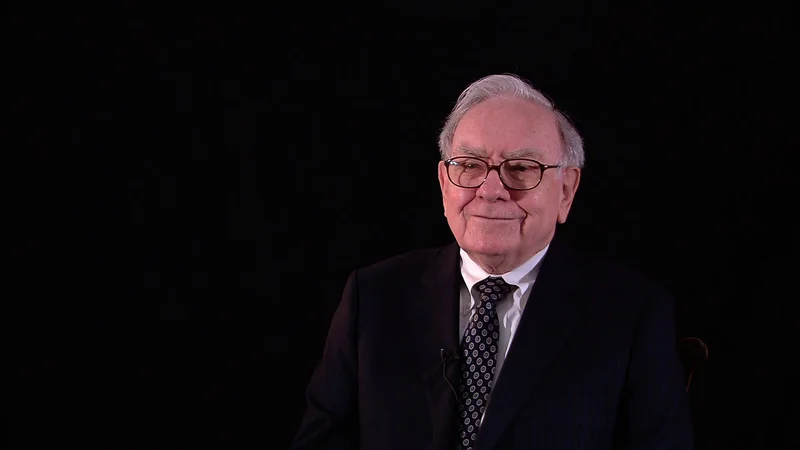

It’s one of the great “what if” scenarios in modern corporate history. Sometime around 2010, two titans of American industry, operating from philosophically opposite ends of the business spectrum, had a conversation about money. On one end of the line was Warren Buffett, the personification of value investing, a man who views businesses as discounted cash-flow machines. On the other was Steve Jobs, the mercurial visionary of Apple, a leader who saw a company as an extension of his own will to create perfect products.

The subject was Apple’s rapidly growing cash pile—"many, many, many, many billions," as Buffett recalled. The question was simple: What should be done with it?

Buffett, ever the pragmatist, laid out the standard playbook for a public company flush with cash: dividends, acquisitions, or stock buybacks. Given that Jobs had no interest in large acquisitions and that he firmly believed his own company’s stock was undervalued, Buffett’s recommendation was clear and mathematically sound. Buy back your own stock. It was, by the numbers, the highest-return investment available to Apple at the time.

Jobs listened. He agreed with the premise—that Apple stock was cheap. And then he did absolutely nothing. The fact that Steve Jobs didn’t take Warren Buffett’s financial advice to buy back Apple stock, and it says a lot about his leadership style, reveals a fundamental discrepancy between two models of corporate leadership. More importantly, it represents a multi-hundred-billion-dollar decision driven not by a spreadsheet, but by the unique psychology of a founder who valued control over capital efficiency.

The Cost of Conviction

Let’s first quantify the opportunity cost, because the numbers here are staggering. In 2010, Apple’s stock was trading for about $7.50—to be more exact, around $7.40 per share on a split-adjusted basis. Today, it trades at over $245. Had Jobs followed Buffett’s advice and initiated a significant buyback program then, the value creation for the remaining shareholders would have been astronomical. A hypothetical $20 billion buyback in 2010 would have retired roughly 2.7 billion shares. Today, those shares would be worth nearly $665 billion.

Buffett’s logic was impeccable. He asked Jobs, "What better can you do with your money?" If you, as the CEO, genuinely believe your company’s shares are trading at a discount to their intrinsic value, then repurchasing them is a demonstrably effective way to transfer value to the shareholders who choose to remain. It’s a vote of confidence backed by capital.

But Jobs, a man known for his “no bozos” policy and an obsessive attention to detail that extended to the screws inside his products, rejected this pristine financial logic. According to Buffett, the reason was disarmingly simple: "He just liked having the cash."

This is the part of the narrative that I find genuinely puzzling. Jobs was not a man who shied away from value creation. His entire career was a testament to his ability to see value where others saw none—in graphical user interfaces, in digital music players, in the very concept of a smartphone. Yet when presented with a clear, quantifiable value proposition for his own company’s equity, he demurred. Why? The answer doesn't appear in any discounted cash flow model. It lies in the operational worldview of a founder-CEO.

A War Chest, Not a Balance Sheet Item

The divergence here is a classic case of misaligned models. For Warren Buffett, a company is an economic entity, and cash is a low-yielding asset. Idle cash is a failure of capital allocation. It’s like a world-class factory running at 10% capacity; the inefficiency is offensive to a mind geared toward optimization. His advice to Jobs was the same he would give any manager of any company: deploy your resources to their highest and best use.

For Steve Jobs, however, Apple wasn't just an economic entity; it was an instrument for changing the world. And cash wasn't an asset to be optimized for shareholder return. It was fuel. It was ammunition. It was a strategic war chest that guaranteed absolute operational freedom.

This cash hoard (which would later swell to over $250 billion under Tim Cook before being drawn down) was Jobs’s ultimate leverage. It meant he would never again have to court skeptical venture capitalists. It meant he could fund the decade-long development of a secret project like the Apple Car without ever having to justify its P&L to Wall Street. It meant he could survive a catastrophic product failure or a global recession without laying off the key engineers he needed for the next big thing.

Buffett saw the cash as idle inventory on a balance sheet. Jobs saw it as the dry powder that ensured he would never, ever have to ask anyone for permission to pursue his vision. What is the precise financial value of that kind of strategic certainty? There is no formula for it. It’s an unquantifiable founder’s premium placed on autonomy. Jobs was willing to forgo a mathematically superior financial return in exchange for something he valued far more: complete and total control over his company’s destiny.

An Irrational, Yet Coherent, Decision

So, was Jobs wrong? From a purely financial standpoint, the answer is an unambiguous yes. The opportunity cost of not repurchasing shares in 2010 is measured in the hundreds of billions of dollars. Any rational CFO, presented with the same facts, would have initiated a buyback.

But Steve Jobs wasn’t a CFO. He was a founder who had been fired from his own company once before. He operated with a different set of priorities. His decision to hoard cash wasn't an analytical error; it was a deeply personal and strategic choice rooted in his own history and his vision for Apple's future. He was paying an immense premium for insulation against the whims of the market and the interference of outsiders.

Could Apple have become the world’s first trillion-dollar company, and then its second and third, without that fortress of a balance sheet? Could it have funded the colossal expense of Apple Park or the massive R&D outlays for its custom silicon without that cash buffer? We can’t run the counter-factual. What is clear is that Jobs made a decision that was financially suboptimal but psychologically and strategically coherent with his leadership style. He chose sovereignty over optimization, and in the end, it’s impossible to argue with the results he produced.